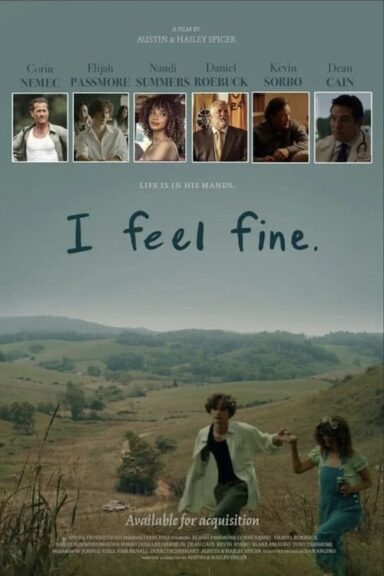

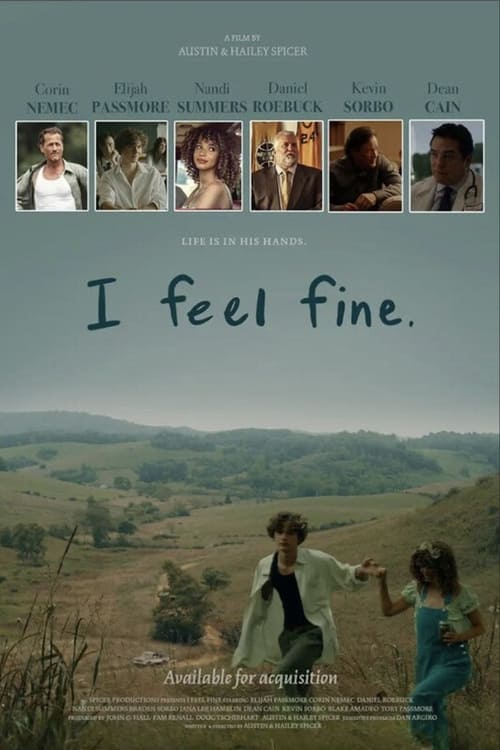

A film by Austin Spicer , Hailey Spicer

With: Elijah Passmore, Nandi Summers, Corin Nemec, Jana Lee Hamblin, Braeden Sorbo, Blake Amadeo, Kevin Sorbo, Dean Cain, Daniel Roebuck, Pam Renall

Ozzy Taylor, a charismatic high school teen, discovers he can’t control his intrusive thoughts of suicide, setting off a life-changing shift in his destiny.

I feel fine is one of those rare films which, because it aims to treat its subject in a way that may surprise, leaves the viewer with a multiple, strange and questioning impression. On the one hand, the film meticulously sets a sunny, luminous mood, wrapping the story in a pop soundtrack that contrasts sharply with the seriousness of its subject. The music perfectly matches the film’s clear intention to evoke this subject in a gentle, benevolent way, and to appeal to the viewer’s empathy so that he or she can enter into the mind of the young man (Ozzy) regarding his relationship with the afterlife; to his suicidal impulse, which invades him, questions him, and against which he doesn’t really fight, because it’s stronger than he is, and because it gives him a blissful impression, making him say, to anyone who will listen, that he “feels good”.

In addition to its melancholy, even nostalgic atmosphere, I feel fine is unusual in how little it focuses on psychiatry, psychology or the “medical” point of view in general, probably wanting to touch on something more universal, beyond the isolated case of Ozzy. Hailey and Austin Spicer seek above all to normalize Ozzy, to make him loving, loved, thus choosing to offer the viewer a reading essentially based on emotion, even sentiment, but also somehow placing the story under a moral angle, with a religious undertone. Surprisingly, the bittersweetness we’ve introduced, which would normally be intended to protect the viewer from an overly immediate, brutal or trivial approach, has a similar effect here: we quickly come to accept the drama as the only possible outcome. If the overall gentleness attaches us to the character and those who love him, the spleen becomes all too perceptible, and the intention to make tears flow unmasked… By extension, instead of moving and gripping us, the process deliberately tends to defuse the dramatic impact. Here, too, the effect becomes twofold, since the aim is to take things philosophically, to open our eyes to a calmer, more conciliatory way of looking at things – like the soothing words of Christianity, which see death as a departure for a better world; a contrast emerges. As the intention becomes clearer, we detach ourselves from a mysterious and captivating part of the story, which we imagined to be raw material, indications or insights, brought to us with subtlety, parsimony and delicacy.

Behind the apparent conditions for fulfillment and happiness, the image of a protective family, there seem to be hidden shadows, things left unsaid that are very hard to bear for the hypersensitive Ozzy. The “happy” life he sometimes feels, the smile he wears on almost every occasion in society, masks a malaise linked to deep-seated anxieties, be it the fear of a bleak future, or some highly disappointing observations about those he loves.

Thus, I feel fine seems to share with us, half-heartedly, that the young man’s spleen could find its origins, in part, in a few dysfunctional family and educational flaws, notably the imperfect, unbalanced relationship between his parents – his mother, a down-to-earth woman, in particular, doesn’t seem totally happy with her husband, a moody, passionate, even absent man; she feels neglected; who maintains a relationship with Ozzy that she sometimes deems irresponsible – but also other reasons for dissatisfaction and even disenchantment. For example, when Ozzy’s sister becomes pregnant by his best friend, Ozzy feels betrayed, but doesn’t express it, especially as his friend is presented to us as a teenager who seeks above all to multiply his conquests, to affirm his sexuality and enhance his image as a seducer with his male audience. Ozzy, very secretly, can only observe what he sees as a lack of respect for him and his sister, and which his family takes much more lightly than he does, without feeling the danger of an inescapable hurtful break-up, as he does.

His hypersensitivity also manifests itself on a daily basis, when it comes to considering his personal horizon. Here, too, he displays a cold lucidity that stands in stark contrast to that of his peers, unable, he admits, to project himself into a bright professional future, or even to entertain the hope of one.

It’s a pity, then, that the drama – probably for the sake of balance, of striking the right balance in the quest for efficiency – and the notorious call to tears, supported by a budding romance, suddenly come back to us, telescoping and superimposing themselves on a naturalistic undertaking, a subtle, profound, delicate and modest subtext, like Ozzy.