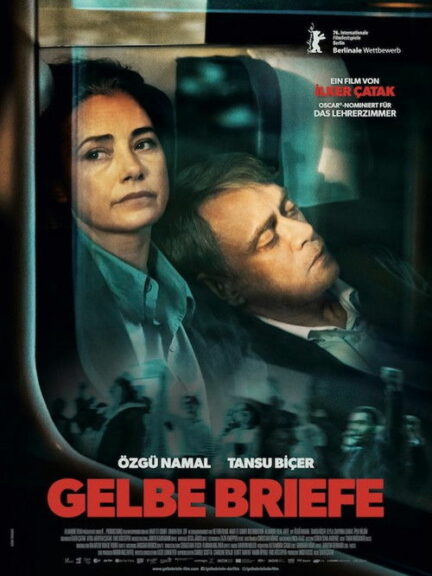

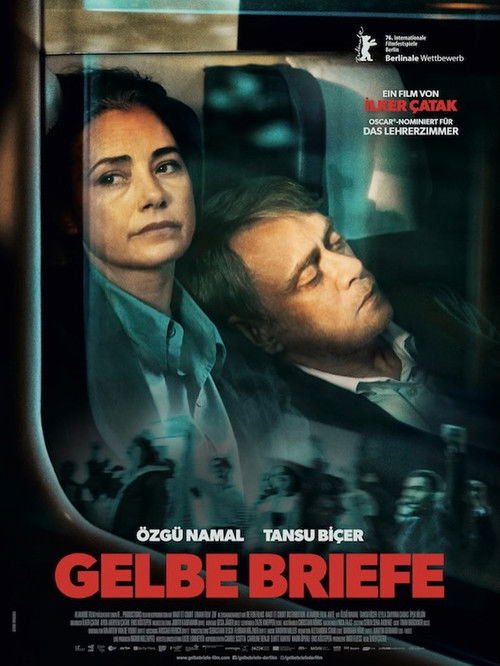

A film by İlker Çatak

With: Özgü Namal, Tansu Biçer, Leyla Smyrna Cabas, İpek Bilgin, Şiir Eloğlu, Eray Egilmez, Marco Kühn, Yusuf Akgün, Kerem Can, Aziz Çapkurt

Life is good for Derya and Aziz, a celebrated artist couple from Turkey, until an incident at their play’s premiere. Suddenly targeted by the state and struggling to balance their ideals with life’s necessities, their marriage is pushed to a breaking point.

Our rate : ★★

Ilker Çatak is one of the local directors competing at this year’s Berlinale. His previous film, The Teachers’ Room, in the parallel selection, made an impression on some German viewers and critics at a previous edition of the festival. Yellow Letters, his new offering, opens with a disturbing sign reading “Berlin as Ankara.” Divided into two parts before its finale, the first in Ankara and the second in Istanbul, filmed in Berlin and Hamburg respectively, the story focuses on a wholly Turkish narrative with no obvious connection to Germany or even the Turkish diaspora. This work tackles several intertwined themes and immediately addresses a powerful political subject, focusing on what is happening in Turkey today under Erdogan: censorship and the persecution of intellectuals who challenge or question the religious authorities in power.

As the film progresses, it weaves a web that opens up other themes, to the point of gradually abandoning what we mistakenly took to be its main subject. As the opening scene (applause following a theatrical performance) suggests Ilker Katak, through his two main characters, then opens a parenthesis that gives prominence to questions about art, its function, the demands it makes, the very nature of the artist, but also the relationship between director and actress-muse, put to the test by the couple and the passing of time. It is a reflection on art and its repercussions in everyday life, a theme dear to Bergman, for example, who constantly used his own autobiographical material to question the artist as a human being. Yellow Letters shows patience (perhaps a little too much) and ventures into a nuanced, rather subtle analysis of the mechanisms that can be found in a couple, where each partner needs their own space and has personal aspirations that can interfere with those of their spouse. From a political subject and a reflection on art emerges a more intimate observation, questioning not only the marital relationship, but also family, education, ambition, and the contradictions that each person carries within them. From a situation complicated by political commitment and strong personal convictions that disturb those in power but unite the couple, insidious discord gradually emerges in a union that appears perfect and solid, but also buried truths, silenced and even inaccessible to the conscious mind.

This intimate, even intimate development, which was not obvious, well served by conscientious actors invested in their characters, probably earned Yellow Letters a place in competition at the Berlinale, even if the bar seems a little too high. The form of the film, which is otherwise rather elegant, particularly in its musical choices, is not out of place, but does not allow for the sublimation of an observation that is certainly interesting but sometimes lacks intensity, to capture our attention more fully.