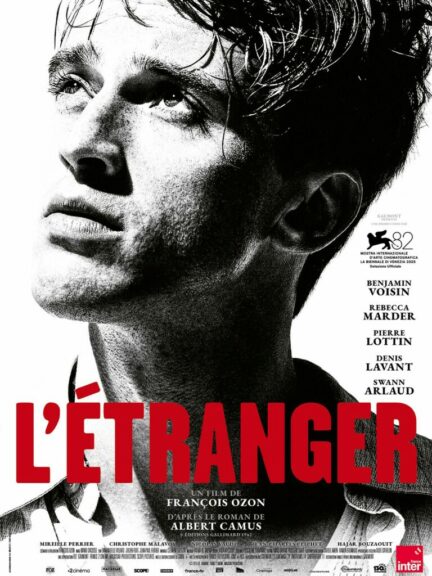

A film by François Ozon

With: Benjamin Voisin, Rebecca Marder, Pierre Lottin, Swann Arlaud, Denis Lavant, Jean-Charles Clichet, Jean-Benoît Ugeux

In 1930s Algeria, Frenchman Meursault’s emotional detachment leads to a murder, scrutinized by a skeptical trial, adapted from Camus’ « The Stranger. »

Our rate 1: ****

With The Stranger, François Ozon offers a perfect adaptation of Camus’ novel: a film that reveals the cinematic potential of this literary masterpiece and shows how Camus’ simple, factual writing style lends itself ideally to being brought to life on screen. Here, the impression of simplicity comes from the fact that everything in Ozon‘s work seems right and natural, everything is well thought out and used in just the right measure: the sparing use of voice-over, the flashbacks, the black-and-white imagery (Manu Dacosse’s sublime work with daylight), the music, the realistic sets, and the powerful yet controlled performance of Benjamin Voisin, who asserts his talent by successfully playing such a complex role. Voisin has understood the role so well that he lives in Meursault’s shoes, as if the character were written especially for him.

More than 80 years after the novel’s publication, Camus’s thinking still troubles us, perhaps even more so today. Watching the film, we find the novel’s position in relation to the colonial context in which it is set particularly disturbing. Furthermore, Camus directly attacks, particularly through the trial sequence, the moralizing spirit of the society surrounding his character. For all these reasons, we appreciate the courageous gesture of having made this necessary adaptation.

Our rate 2: **

The Stranger is consistent with Camus’ thinking, and in this respect, it questions as much as it disturbs, due to the few clues it gives as to how to interpret it, and the ambivalence of its demonstration, which is both simplistic and terribly complex. It is as if one needs to be armed to understand absurdism, Camusian thought, which distances itself from existentialism and nihilism. Like many, Ozon admits that he read the book too young. We did too, and we haven’t revisited the book since, at most reading different opinions on Camus, 65 years after his death, which have fueled opinion columns. He embarked on this adaptation because he was frustrated at not being able to mount a more personal project, a story about suicide; returning to Camus seemed obvious to him, a challenge all the more interesting to take on because many people advised against it, arguing that it was impossible to adapt The Stranger for the screen, since even Visconti himself had failed to do so (Ozon added in a press conference that, in his opinion, the project should have gone more naturally to Antonioni).

By sticking fairly closely to Camus’s thinking, without pushing it too far, but rather putting it into context and skimming it, François Ozon’s adaptation brings us back to the initial impression left by the book. That of having a beautiful film (or text) serving a thought that is disturbing, with its different levels of interpretation and formal biases, complex and simple at the same time, denouncing without denouncing, exposing a morality (or lack thereof) that questions itself. The point of view taken (that of the guilty party) is even more disturbing—which is indeed the aim—since little attention is ultimately paid to the victim, referred to as “an Arab,” that is, as a second-class citizen in the context of the time (and, we might be tempted to say, in today’s context as well). Ozon, wanting to put this into context, begins the film with archive footage of French Algeria, accompanied by the exotic discourse of the time. He also makes it clear that cinema in Algiers was forbidden to “natives.” The Stranger retains a few sentences and passages from the film, but only uses a few revealing excerpts, and the overall plot. Ozon prefers to add two scenes that are not in the book, but also to avoid using a voice-over throughout the film (as Visconti had chosen to do in his adaptation). The man we see, who is the first to be surprised that he feels nothing, aims for the extreme act that will condemn him. But this imprisonment will be almost a liberation for him, allowing him to feel alive, to feel, to understand that he had been happy and that he loved Marie on the one hand and his mother on the other. This call for understanding of the killer’s psychology, this explanation of the text that questions the surrounding context, goes hand in hand with a condemnation of the era (we are all guilty, we are all condemned). This is precisely what can escape us and resist our ability to hear the power of the text, the reasoning, and the genius of Camus; since what would naturally have been in the foreground (madness, the criminal act, the victims’ point of view) is relegated to the background, and the reader/viewer must bring it back to the forefront of their thoughts (Meursault’s indifference reflects their own indifference). Other great writers such as Dostoevsky (Crime and Punishment or The Brothers Karamazov) have also strived to penetrate the criminal’s train of thought (or that of the innocent man who considers himself guilty, Dimitri Karamazov)? Still others have explored the mind of the desperate man who reflects on what his life has been and what his last days will be (Brazillac, Le Feu Follet). These writers do not produce the same effect of aversion or excessive distance that can disturb us in Camus’s concept. Dostoevsky’s literary approach demonstrates a desire to understand in order to forgive, a very strong moral vision that is more accessible. In Camus’s approach (but also in Sartre’s), on the contrary, there is a desire not to seek understanding, as if the cause were lost in advance, a form of defeatism and renunciation, an abandonment of the moral question on the principle of “what’s the point?” yet Dostoevsky was a nihilist… On this point, we agree with Ozon when he says that the filmmaker who would have been best suited to adapt Camus would have been Antonioni. If we consider The Passenger, in which a character puts himself in danger in order to breathe and live again, we are not so far from Camus.

But with The Stranger, the concept goes much further, with the death drive going hand in hand with the life drive, to the point of legitimizing the death drive, or the death of the other itself. This is disturbing, especially since, as we read, it is up to the viewer (the reader) to form their own judgment, and this great openness, which we find here, requires maturity to be fully understood. And perhaps it is at this level that The Stranger remains unadaptable, because for the rest, Ozon leads us to think exactly the opposite, as Camus’s finely crafted writing seems to have been designed for cinema (like Japrisot, for example). Finally, let us add that François Ozon‘s suggestion to Benjamin Voisin to review Bresson’s cinematographer’s notebook was indeed a good way to approach Meursault, but that his choice to film Rebecca Marder and Benjamin Voisin physically is more questionable, and that black and white, while allowing for transposition to a different era, has two disadvantages in relation to the text: it fails to convey the omnipresent blue of the sky and sea, or the dazzling light of the sun and the city of Algiers (here replaced by Tangier for filming).