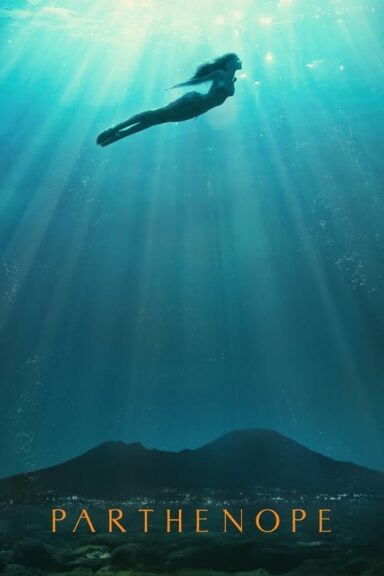

A film by Paolo Sorrentino

With: Celeste Dalla Porta, Stefania Sandrelli, Gary Oldman, Silvio Orlando, Luisa Ranieri, Isabella Ferrari, Silvia Degrandi, Lorenzo Gleijeses, Daniele Rienzo, Dario Aita

The long journey of Parthenope’s life, from her birth in 1950 till today. A feminine epic, devoid of heroism but brimming with an inexorable passion for freedom, Naples, and the faces of love—all those true, pointless, and unspeakable loves.

Our rate: ****

Here, Sorrentino delivers a film that sums up his work, as filmmakers regularly attempt to do, with varying degrees of success (good points for Holly Motors, for example). Nevertheless, he takes the liberty – and the credit goes to him for doing so – of taking into account frequent feedback on his « m’as tu vu » style, and, in fact, of trying out new things while maintaining his guideline and tightening up his film on his know-how, his view of the world, and his relationship with cinema.

Gentle as ever, despite its usual perversities, Parthenope acts like the mythical siren so closely linked to Naples, from which it borrows its title, its inspiration and its movement: it magnetizes throughout, and constantly plays on this magnetism until it confuses us. From this declaration of love-hate to Naples the beautiful, its splendor, its follies, its magnetism despite all its filthiness, Sorrentino delivers many reflections on beauty and intelligence, the meaning of anthropology – even quoting his master on the subject Billy Wilder :-), the virginity of mermaids, the desire of old people and the fantasy that the most intelligent among them remain seductive and seductive. Of course, he also takes advantage of the opportunity to decipher tartuffery, to amuse himself with philosophical maxims that can be taken or left. Of course, Naples la belle is also Napoli (without Maradona here). Parthenope aims to do all this (or, as the film itself puts it, it’s just a scam, with Sorrentino showing a certain distance from his naturally pretentious inclination, which has often played tricks on him), and in so doing offers a notable artistic gesture – at a time when this ambition to consider cinema as an art rather than a medium is tending to disappear more and more.

Sorrentino seems at peace with himself, still self-confident but more open, finally refraining from overkill, with a more balanced dose of pathos and effect, finally stopping his beautiful images and refraining from the futile camera movements that made his reputation, but also constituted an obvious limitation. Parthenope’s setting should earn him an award.