A film by Abel Gance

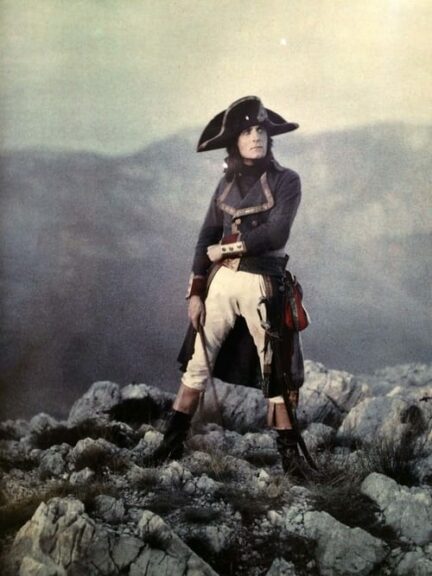

With: Albert Dieudonné, Vladimir Roudenko, Edmond van Daële, Alexandre Koubitzky, Antonin Artaud, Abel Gance, Gina Manès, Suzanne Bianchetti, Marguerite Gance, Yvette Dieudonné

A biopic of Napoleon Bonaparte, tracing the Corsican’s career from his schooldays (where a snowball fight is staged like a military campaign) to his flight from Corsica, through the French Revolution (where a real storm is intercut with a political storm) and the Terror, culminating in his triumphant invasion of Italy in 1797.

Our rate: ****

Napoleon (as seen by Abel Gance), as it has been renamed, didn’t wait for the Cinémathèque to embark on a reconstruction before being preceded by a reputation as a first-rate, majestic work, a mad gesture by a filmmaker who is undeniably seeking to impress, while at the same time testifying to his great fascination with the figure of Napoleon, what he represents, but also what he transmits through him, and which refers to the author’s own gesture, the megalomania of a man who sets himself an immense challenge that becomes his mission, a man who aligns all his gestures in a single goal that he has given himself, against all odds, and whose only guide or master is himself. In his correspondence with Gance, Céline insisted that only one filmmaker could adapt his most famous work – and perhaps his most complete – his voyage au bout de la nuit. The project never got off the ground, although Gance was relentless in his pursuit of the project, reminding him of how admirable he had found Napoleon, an artistic gesture of the highest intensity. Another great writer, Antonin Artaud (as Marat), praised Gance’s merits, all the more so as one of Napoleon’s interpreters. To hear colleagues tell us that this is a major work, Costa Gavras, in his capacity as president of the cinémathèque, present it as one of the best films in the world – while pointing out that, in his opinion, it’s much more a work of poetry than a biography of the emperor, His colleague at the cinémathèque, Frédéric Bonnaud, points out that the newly-restored version is not the 53rd restoration (many cinephiles have seen previously restored versions – which was not our case until now, with highly variable lengths), and we were keen to attend this premiere – the first 3h40 part of a film that is 7 hours long, as Gance wished – as part of the inauguration of Cannes Classic, which at the last two editions had already spoiled us with the sublimely restored copies of La Maman et la putain and L’Amour fou, both of which were unbelievably intense films. From the prologue, devoted to Napoleon’s childhood, the artistic (and narrative) gesture is obvious and admirable. Abel Gance insists on taking his time to bring us as close as possible to a man (then a child) different in his ambitions, his posture, his foresight and his bravery, a leader of men like no other, who doesn’t let himself be impressed and loves combat and difficult situations. Abel Gance‘s style also asserts itself, with mise-en-scene and editing becoming de rigueur.

The film’s title, Napoléon as seen by Abel Gance, and Costa Gavras‘s introductory presentation, seemed to be intended to deflect us from any criticism Ridley Scott may have recently levelled at Napoléon for its liberties with history. Instead of this usual precaution and poetic emphasis (yes, visually the film offers a highly artistic visual anthology, like Fescourt’s Les Misérables – a contemporary of Gance‘s, or Bondartchouk‘s War and Peace, some forty years later), we prefer the presentation that Gance himself gives us from the opening credits: a cinematic epic. His primary intention was to put an epic, a destiny, into images, to artistically enjoin images that would corroborate what the character portrayed – an uprightness, a posture, we might say. While many novel adaptations of Napoleon’s life have fallen flat on their faces (with Christian Clavier and, more recently, Joachim Phoenix, for example), Abel Gance succeeds, through his direction of the actors, and through the words he retains in the few narrative panels, whether with the young actor in the prologue, or with Albert Dieudonné, to deliver a credible portrait, as epic as it is tempestuous, based on the many historical texts he cites (starting with the writings of Napoleon himself). In the three hours and forty minutes of this first part, we discover the young boy’s very first battle (which may well have inspired Jean Vigo 6 years later (Zéro de conduite)?), Napoleon’s distant participation in the revolution and the convention, the battles in the Corsican maquis, and the battle of Toulon. 3h40 to be compared with the 20 minutes of Scott‘s recent film, which takes up two of these 4 episodes. It’s an over-the-top, over-the-top gesture – which sometimes suffers, but is so often majestic. A work of goldsmith craftsmanship, sublimated by a magnificent technical restoration, and a sound score on the whole in unison with the film, grandiloquent and majestic, over-saturated, which we are unfortunately unable to verify if it reflects the sound intentions given by Gance during the various screenings in 1927.