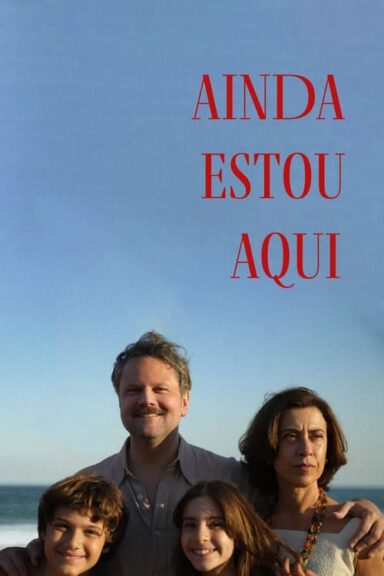

A film by Walter Salles

With: Fernanda Torres, Fernanda Montenegro, Selton Mello, Valentina Herszage, Maeve Jinkings, Dan Stulbach, Humberto Carrão, Carla Ribas, Maitê Padilha, Guilherme Silveira

In Rio de Janeiro in the 1970s, during the dictatorship, former deputy Rubens Paiva was taken from his home by soldiers to be interrogated. He was never found again. The search for truth lasts 30 long years. And when the answers begin to appear, Eunice Paiva feels the first symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

Our rate : **

Walter Salles, who had almost disappeared, returns to Venice’s Sala Grande with a film on a subject that is a recurrent theme in South American cinema: the return to the dark days of military dictatorship, torture and the disappeared. From the very outset, the director of Central Do Brazil reveals his intentions, placing his story essentially on the heartstrings. He introduces a wealthy Brazilian family, living the Western way of life, with joy and good humor. The girls go out, dance to European sounds and dream of Europe, the young boys hone their soccer skills on the beach, others play beach volleyball. The beach party, the close-knit family, the friends and the collective atmosphere, the belief in a radiant future supported by carefree youth, yet the military regime threatens this equilibrium, whether we’re talking about the helicopters flying over Copacabana, or the authoritarian arrests and searches carried out by the police on the way back from the beaches, in search of identified enemies of the regime, suspected terrorists. We also quickly realize that Walter Salles wants to linger over his story, to give himself a chance to grab us, to move us. It should be said at the outset that this true story, like so many others in Brazil (20,000 disappeared), has two attributes that enhance its cinematic/dramatic potential. Firstly, the fact that this story was able to be revealed and documented, notably in the very moving period photos that the final credits gracefully restore to us. Secondly, the fact that the story’s main character is self-evident, with no need for artificial elements. The struggle waged by the wife of the deceased was conducted with the utmost dignity, and she went so far as to take up law studies and become a prominent representative of an equally important cause in Brazil, the defense of indigenous peoples. Salles spends very little time on this, preferring to dwell on the few motifs he has decided to develop: the family, the interrogation, the anguish of not knowing, the preservation of the family’s equilibrium, but also the obligation to live in secrecy, to protect others, within the family unit – the youngest, so as not to terrify them – but also within the group of friends, in the name of the political cause, of the wider struggle being waged, and in the context of a permanent threat, a sword of Damocles hanging over every person who could in any way be linked to the anti-regime struggle. Salles certainly manages to move us at times and in his finale, but he could have done so much more intensely if he had opted for a shorter running time, if his staging had gone in search of other possibilities and if he had been a pioneer or an alarm bell ringer. Here, however, he simply adds another film to the list, without adding anything formally or intellectually to set it apart. This impression of déjà-vu stays with us for 2.5 hours.