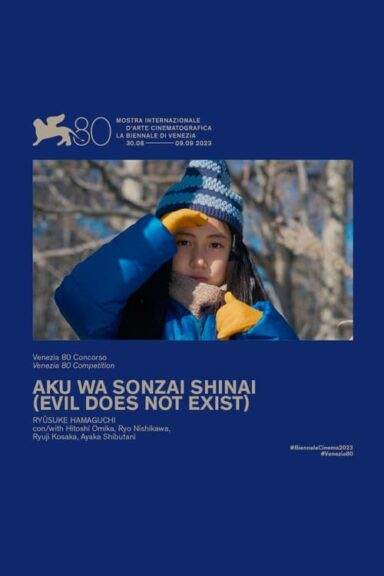

A film by Ryusuke Hamaguchi

With: Hitoshi Omika, Ryo Nishikawa, Ryuji Kosaka, Ayaka Shibutani

A Mizubiki Village, close to Tokyo were Takumi and his daughter Hana lived. One day, the village inhabitants become aware of a plan to build a glamping site near Takumi’s house, offers a city resident and its affects Takumi’s life.

Our Review: *

Hamaguchi, after making a name for himself with his wide-ranging, multi-themed narrative formats, had begun to tighten up his cinema to a short form, with his Wheel of fortune and other fantasies, which brought him closer to Rohmer, or his self-assumed Korean disciple, Hong San Soo. « Let’s hope that, like the Korean director, Hamaguchi also knows how to handle styles so well, and constantly tries out new forms to show the intimate light of which he is a master, and whose poetry we feel, » we concluded in our review of Wheel of fortune and other fantasies, which won over all our reviewers when his previous works divided us more. Evil does not exist continues this fox-like approach, to quote Michel Ciment, to new forms. From the very first images, Ryusuke Hamagushi indicates that he is resolutely moving away from the narrative breadth of Drive my car or Asako, towards a cinema of gesture and precision, a slow cinema that borrows more from Keilly Reichardt than from Bresson; leaving plenty of room for raw sets, for characters rooted in their function, questioning the existence and function of man on the planet, a critical rather than pamphleteering cinema that advocates a cause, delivers a simple, limpid message, all the while trying to surprise narratively and insert deceptive sub-contexts, to propose emotional reflections as in all Hamagushi‘s work, but this time, clearly in the background. The result doesn’t dazzle us: the opening scenes, in imitation real time, where a man – who will later turn out to be our hero – chops wood near a river, certainly set the mood, but the arrival of city-dwellers in this relatively unspoiled provincial territory, where deer can still make their way through the forest, threatens the balance of nature, but also of the film… It’s a mistake to think that the film is taking a turn towards the kind of protest cinema that likes to portray the ridiculous, to support a farce based on decisions made by the few to the detriment of the settled population. One might think, then, that Hamaguchi draws his inspiration from the scalpel-like cameras of Radu Jude or Mungiu to deliver either a farce or a pamphleteering trial of the way the world works… Starting from a situation, developing it, exaggerating it, concluding, such could have been the narrative framework. But instead, and disconcertingly, Hamaguchi develops another story, that of two people who have come to act as intermediaries with the local population, on the orders of the boss of a company who wishes to invest in « Glamping » (glamorous camping) … their conversation in the car, on a journey between the town and the countryside seems to follow the same trajectory as Drive my car, in which each person opens up to the other and reveals his or her most intimate side, by chance and through other reflections. All this could have been quite intriguing, in the good sense of the word, if there had been a thread linking the situations more precisely, if there hadn’t been this return to the initial situation, to the problem raised. Admittedly, Hamaguchi manages to create a form of false suspense by taking up his story a little where he left off, but generally speaking, he loses us with him, for having followed paths too different from one another, not having gone to the end of any of them, and above all, not having made a strong choice of direction. Right down to its title, Hamaguchi delivers a film marked by hesitation, or an introduction to what it could have been but ultimately isn’t, ultimately highlighting more its shortcomings (notably radicality, provocation, confrontation, strength, complexity) than its qualities (finesse, a sense of detail, observation, reflection on the way the world works, simplicity).