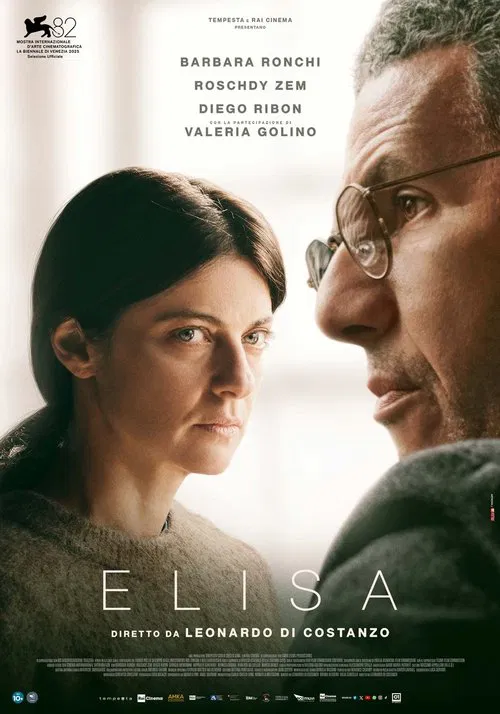

A film by Leonardo Di Costanzo

With: Barbara Ronchi, Roschdy Zem, Diego Ribon, Valeria Golino, Giorgio Montanini, Hippolyte Girardot, Monica Codena, Roberta da Soller, Marco Brinzi, Nadia Kibout

Elisa, the daughter of an ordinary family, has been in prison for ten years for brutally murdering her sister. She believes she doesn’t remember what happened, but her fragmented memories begin to come into focus during meetings with the criminologist Alaoui, who is conducting a study on family homicides. The truth that emerges for Elisa is devastating—a pain that may mark the beginning of redemption.

Our rate: **(*)

An intelligent narrative that attempts a relatively complex stylistic exercise, constantly seeking to vary the initial approach of psychoanalysis of a particular individual, but which seeks to question and understand violence in a more general way. Leonardo Di Costanzo defends a vision that runs counter to what the current era tends to promote. He opposes a rather simplistic view (violence must be suppressed, we must lock up criminals) with a vision that may seem simplistic, but whose strength, conveyed to his double embodied by the character played by Roschdy Zem, lies precisely in bringing out its complexity with humility. The cause of violence is, above all, multifactorial. Of course, family and societal context play a role, but more personal factors also come into play, both psychological and psychiatric. Simple emotions such as fear, anger, and frustration play an important role in triggering the act, and a poor reading or understanding of one’s emotions makes it impossible to avoid or control them. The film thus opens with a striking lesson in criminology, where characters do not feel guilty about a heinous act because they feel they have done justice and are therefore in the right. This reflection, applied to a person or a country, is at the very heart not of the film’s demonstration, but of the points it raises. In the end, the film delivers its answers, after carefully revealing its narrative elements little by little to keep the viewer alert. These answers may seem naive to some, but they deserve to be taken into consideration, as repression cannot be the solution and has proven to be ineffective. It is a pity, however, that Di Costanzo did not choose to make a powerful film, as Sydney Lumet would certainly have done, given his interest in very similar themes. Nevertheless, we understand that, aware that he was presenting an alternative that many would instinctively reject as idealistic, naive, or even dangerous, he sought to avoid causing double offense.