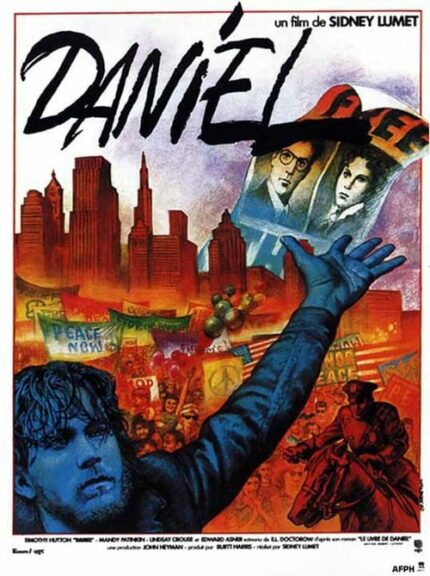

In the mid-1950s, Rochelle and Paul, American communists, were accused of spying for the USSR. Fifteen years later, their daughter Susan becomes a political activist. Her brother Daniel is trying to forget. But a tragic event forces him to delve deeper into his family’s history…

Sidney Lumet, a major filmmaker, is rarely mentioned when we talk about the New Hollywood, where new American auteurs, inspired by the French New Wave, wanted to take up the cameras to tell the story of an America that was not that of the Studios, an ideologically politicised and gangrenous America, an America eaten away from the inside, with its abandoned and its share of torments. Cassavetes, Coppola, Scorcese and his screenwriter Schräder, De Palma, Bogdanovitch, Kubrick, Pakula, Ashby, Friedkin, Altman, Hopper, Altman, Lucas, Spielberg and Cimino are the names most often mentioned. But alongside them, two Sidney, to whom the Lumière Festival has paid tribute over the last two years, in relation to the breadth of their filmography, which is less well known, or known only in part – we can say that they are far less revered than the first mentioned – are works that are partly more accessible, partly more difficult. Many people only know Lumet‘s flagship works, those starring Al Pacino, Dog Day Afternoon , and even more so Serpico, his first film Twelve Angry Men, his latest, Before the devil knows you’re dead, which rather awkwardly takes up the basis of Dog Day Afternoon, and his musical comedy starring the two child stars Michael Jackson and Diana Ross, The Wiz.

In the meantime, however, Lumet has produced a number of masterpieces of particularly meticulous writing, with different layers that stand out for their ability to capture, render, amplify and above all question, deeply question. Equus and The Network, for example. Who can forget that Lumet also had a regular place at the Cannes Film Festival before the 1970s, with three films: Long Day’s Journey Into Night, The Hill, The Appointment, and then again in 1992 with A Stranger Among Us, in Berlin, where Twelve Angry Men went home with the Golden Bear in 1957, and where That Kind of Woman was screened in 1959, The Pawnbroker in 1964, The Group in 1966 and then 40 years later Find Me Guilty , or finally that the Venice Festival invited The Prince of the City into its selection?

It’s good to discover or rediscover Lumet‘s work, to immerse oneself in the complexity of his cinema, at a time when industrial cinema is tending to become more standardised than anyone could have imagined, when new auteurs are marginalised, restricted in their ambitions, and old auteurs sanctuarised to the point where they can no longer offer anything other than what they have already offered, and yet, perhaps more than ever, the world is moving in an unknown direction, fraught with danger and deleterious. More than ever, new compasses are needed, and we can only expect them from art, since the politicians, religions and capitalist system that are calling the shots can only be blamed. How good it is to be offered in cinemas a restored version of a Lumet film that has been unfairly kept secret, so obvious are its qualities that it bears witness to a bygone era, alerts us to it, and echoes and resonates with our own, born on the ashes of its evanescence, but which reproduces its failings, like a recurring cancer. It’s so good to be able to rely on close observation, on a frontal criticism that doesn’t hide, that isn’t hindered in any way, and that presents things in their complexity and not in the reductive or short-sighted way that the media hubbub imposes on us (Lumet was so right with The Network…). Daniel, the title that perhaps inspired Ken Loach and his I, Daniel Blake, denounces America and its system of thought, just as the English director denounced the British system, but in incomparable styles, except that both, in speaking of a localised situation, manage to grasp the universal question that surrounds it.

Daniel allows Lumet to tackle a subject that shook post-war America, when the Cold War was the new threat, and the American vision had to prevail over any doctrine to the contrary, generating a witch-hunt in the country that may have been unprecedented: the case of the Rosenbergs, accused of spying for Russia in connection with their left-wing activism, and liable to the death penalty.

We feel it is important to warn our readers who are unfamiliar with this case, and its fate, to proceed in a strict order: first discover the light Lumet sheds on it, especially without knowing the outcome, then find out more to form your own opinion. This is essential to the reception of the film, which strives to respect a dual chronology that keeps you on the edge of your seat. [Unfortunately, this pleasure was denied to us because of the presentation that preceded the screening, which was certainly very enriching and enthusiastic, but which in fact prevented us from seeing the film untouched.]

Contrary to what may be read here or there, which is certainly understandable, Lumet does not question the actions of the Rosenberg parents – some like to draw a parallel with what they see as the present radicalisation of left-wing ideals, and thus, in spite of themselves, express their own political opinion – but the death penalty, American society as a whole, its many dysfunctions, whether on the psychiatric or justice side. What’s more, the director’s gaze matches that of his hero, Daniel. He conveys his malaise, his suffering, his path to self-realisation, and above all shows us the very strong and indestructible bond that unites him with his sister. They are the only ones who can understand each other, no outsider can live in the same reality and judge them, the collateral victims.

Lumet adapts The Book of Daniel by E. L. Doctorow, who also wrote Ragtime, which was adapted by Forman, using an elegant and dizzying narrative device. The elegance and vertigo stem from the choice to focus on the inner self of this young man, affected, wounded, seeking to understand his emotions and the world around him, and to portray the violence of the outside world with rare force, But he also tells a very intimate story about his alter-ego, who is going through the same issues and experiencing things in a different way. Daniel will not be able to integrate painlessly into American society without an introspective journey that can explain the shadows of the case, his own demons. In his quest for inner peace, he comes face to face with one of the greatest paradoxes of all, that of loving his sister, but no longer being able to suffer from sharing his suffering with them, of having to free himself from it.

Beyond the political question, Lumet and Doctorow touch on an imminently complex psychological issue, showing, more than ever, that a common trauma does not necessarily produce similar effects on individuals, depending on their vulnerabilities and personalities. The defence mechanisms that are put in place – denial, fury, anger, distancing, the need to assert oneself, the need for recognition – combine with simple aspirations: to be loved, to love, to build oneself, to find one’s place. First to survive, then to live.

Lumet‘s camerawork and Doctorow‘s words (the dialogue is remarkably precise and intelligent) also allow us to grasp the issues surrounding the psychology of Daniel and his sister. What does society propose to do to help them? What can it do? Is it possible to heal a deep-seated illness? And here, the vertigo stems partly from the thread that separates Daniel from his sister – he will stay on it, she will fall off it – and partly from the sensitive question of how others view their ill-being. It also has to do with Daniel’s emotional journey, which will lead him to question himself as soon as he feels guilty – despite himself, because his intention was to help – for his sister’s slide into self-destruction. The psychiatric institution and society’s judgement are then metaphorically and masterfully mirrored by the original fact, the American legal institution. The idea is to put people to death, to condemn them, to exclude them because they express opinions that the majority consider dangerous. Stifling, silencing, excluding, then putting to death, directly or indirectly. Finally, it’s about the element of chance that makes a person fit into society, thrive in it or be crushed by it.

Sidney Lumet succeeds in the very difficult challenge of combining intensity and finesse of observation, to offer us a strikingly acute triple portrait (of Daniel, his sister and America). He also succeeds in the equally difficult formal challenge of confronting images from the past with images from the present (in 1983) and managing to link them seamlessly, without the rhythm even suffering because disruption is set up as the main concept. He finally succeeded, though he could not have predicted it, in making his film 40 years later, unearthed from who knows what attic, offer a new vertigo, that of confronting not two, but three eras, 2023, 1983 and 1953, to arrive at this inexorable observation: things have changed in appearance, but the same phenomena continue to be observed, the same stimuli provoke the same reactions.

Lumet considered Daniel to be his best film, but the critics dismissed it as humanistic, ideological and naive. Yes, Lumet spoke to us of love, of an imperfect world and hoped for a better one (what a utopia!), but at the same time, how can we speak of naivety when the observations made were so bitter, so brutal and, in a way, misanthropic? Lumet‘s humanity in focusing on the feelings of the neglected is simply a response to the kind of humanity he loathed, the kind that leads people to be blind, to sweep dust under the carpet, to pretend there is no problem, or to displace it. This theme haunted him, just as it haunts us in Daniel This little light of mine‘s final score, played by Caroline Doctorow (the novelist’s daughter), or in Timothy Hutton‘s remarkable performance, whose moist eyes seem to ask the question: if an individual breaks down and turns against society, whose fault is it really, the individual’s or society’s? Daniel’s tears precede our own, in a superb final shot that reconciles the young man with hope, with his past, echoing the film’s opening, which is also passionate and beautiful. It’s strange, then, that Daniel has remained invisible for so long, so much so that it encapsulates the best of Sidney Lumet. Daniel is Equus, The Network and even Serpico rolled into one.