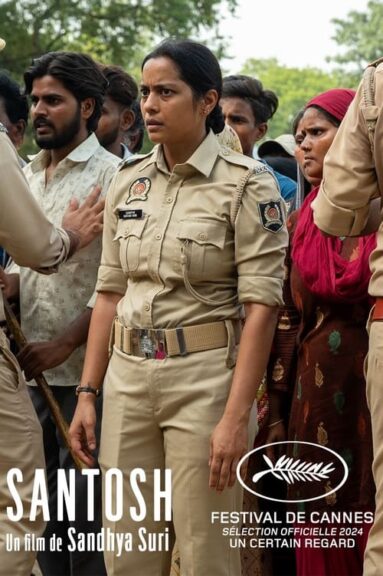

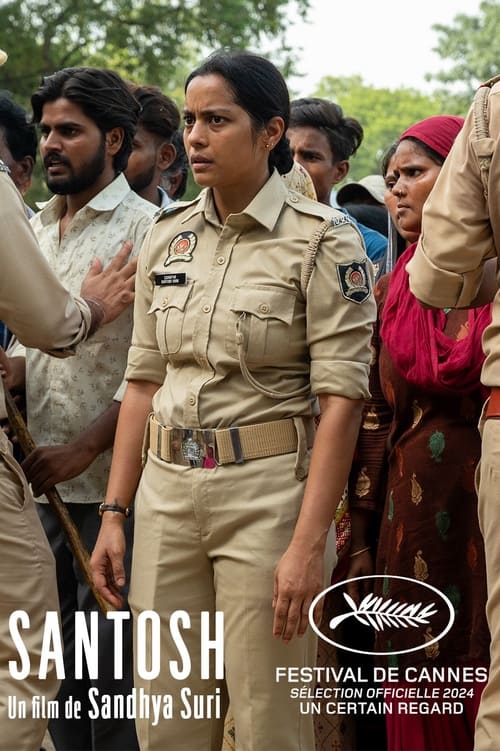

A film by Sandhya Suri

With: Shahana Goswami, Sanjay Bishnoi, Sunita Rajwar

A government scheme sees newly widowed Santosh inherit her husband’s job as a police constable in the rural badlands of Northern India. When a low-caste girl is found raped and murdered, she is pulled into the investigation under the wing of charismatic feminist inspector Sharma.

Our rate : ***

Sandhya Suri‘s Santosh, presented during the Un Certain Regard screenings, is the second Indian film directed by a woman to be selected for Cannes 2024, along with Payal Kapadia‘s All we imagine as light, which won an award in the Official Selection. This women’s detective story sweeps away a few clichés about the exoticism of Indian films by portraying the discreet yet effective Santosh in present-day India. This housewife, widow of a policeman to whom she has given no children and whose family no longer wants her, inherits her husband’s job. She accepts to support herself. When she joins the women’s brigade headed by Sharma, her life is turned upside down. Enthralled by the power and strength of this female leader, she sets out to please her by trying to solve a case involving Dalits (« Untouchables »). However, her investigation will reveal an entirely different truth from the one she expected.

Breaking with the cliché of the reclusive wife, preparing spicy dishes in a colorful sari and variegated veil that populates the films of Satyajit Ray or the Bollywood imagination, Santosh offers a new take on the Indian woman. This time, she’s trivially dressed as a cop, her hair tied back in a ponytail, armed and wearing pants. She travels in a patrol car or on a motorcycle with her partner, just like any other movie cop, except that the backdrops are those of a colorful Indian provincial town and its poor suburbs. Directress Sandhya Suri explains that the idea for the film was in fact born of a photo taken in Delhi during the protests following the Nirbhaya gang rape case. » The photo showed a huge crowd of angry protesters, their faces contorted with rage, and facing them, a line of policewomen forcing them back. One of them had such an enigmatic expression that it fascinated me. When I started researching women police officers, I learned about the government program under which dependants of deceased police officers can inherit their jobs« . It’s the depiction of these incredible journeys of women who don’t leave home without their husbands or parents, who overnight enter police training where they take on the whole of society, that makes Santosh fascinating and new.

This apprenticeship takes place through the relationship between two women of opposite character and, by necessity, strong character. Santosh (Shahana Goswamien, with impeccably measured acting that alternates harshness, gentleness, energy and restrained anger) is just starting out in the business. She is overly motivated and convinced of the merits of her mission, in which she exceeds all expectations. She is taken under her wing by Sharma (Sunita Rajwar, a character both human and ambivalent about power and sexuality), a charismatic chief who is credited with being one of the first female police officers to pioneer the development of women’s brigades. As Santosh discovers the inner workings of society, she also discovers its darker side: the corruption of omnipresent, ruthless, systemic, unisex violence.

This violence is expressed here first and foremost in the invisibilization and treatment of wives in Indian civil society, and in the brutal conversion of unfortunate widows into peacekeepers. It then bursts forth in Santosh’s discovery of the violence of the population through the murders perpetrated in particular against women, and the violence of the police’s relations with this population. The exemplary case of the rape and murder of a young woman from the Vaishya caste (a bourgeois merchant class) reveals to Santosh the unequal, exclusionary and violent underbelly of police work and the exercise of power.

Without complacency, the film dismantles the entire social mechanism and exposes the workings of institutions which, while claiming to ensure justice and perpetuate violence in a system of survival, corrupt the women they enshrine to the core, before sending them back to nothing. A striking, spectral sequence of hallucinatory torture, worthy of a war film, of a Dalit man accused without proof of murder, crystallizes this awareness of social violence, which seeks not so much justice as the ideal, designated scapegoat, incapable of defending himself. Carried away by this logic of class relations and the desire to do the right thing, Santosh initially loses her way.

This latent violence is expressed in the image by a feeling of anxious expectation, which comes from intense close-ups of Santosh and Sharma’s faces, or wide shots scrutinizing the imbalance of bodies and situations, when it doesn’t explode in fragmented editing. The loosening of behavioral and ethical frameworks is further reflected in the saturation of colors, movements in the frame, and the omnipresent, teeming sounds of everyday life in the soundtrack, making the atmosphere ooze and intranquil. This radical portrait of Indian society turns two exclusions on their head: that of women and that of the Untouchables, the outlets of social pressure.

Sandhya Suri, in this feminist and humanist film, doesn’t spare women either. The female hierarchy portrayed here appears just as corrupt as the male hierarchy, in the tradition of the detective film. By definition, power corrupts, so it doesn’t spare women. A moist ambiguity of doubt and guilty conscience characterizes Santosh’s path to emancipation, as she discovers unsuspected freedoms and qualities in her job, but also its exorbitant price: responsibility and choice in a world open to all possibilities, including horror. Without concession and with rigorous irony, Santosh shows, without embellishing, an initiatory journey that values the integrity of its heroine in the face of the intrinsic violence of the world, making it positive and civic-minded.