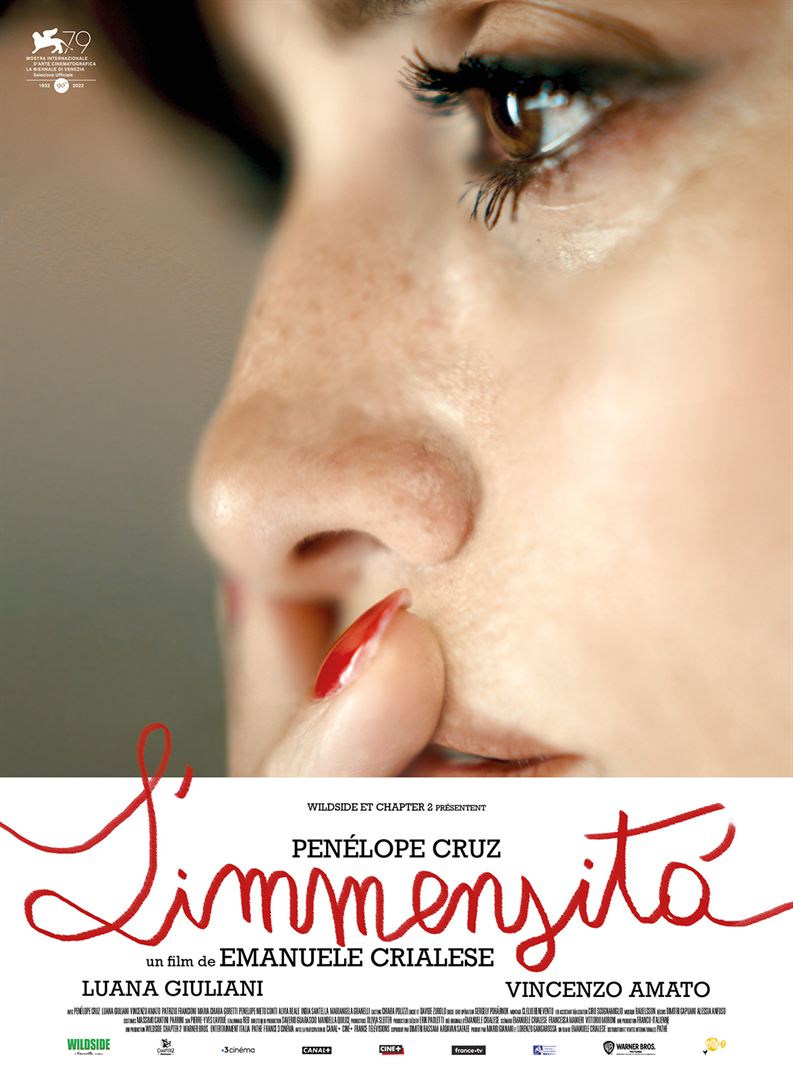

Rome, 1970s: a world suspended between neighborhoods under construction, television programs still in black and white, social achievements and family models now outdated.

Clara and Felice have just moved into a new apartment. Their marriage is over: they don’t love each other anymore but they can’t separate. Only their children, on whom Clara pours all her desire for freedom, keep them together. Adriana, the eldest, has just turned 12 and is the most attentive witness to Clara’s moods and the growing tensions between her parents. Adriana rejects her name and identity and wants to convince everyone that she is a boy. Her obstinacy brings the already fragile family balance to a breaking point.

As the children wait for a sign that might guide them – a voice from above or a song on television perhaps – everything changes around them and within them.

Despite some good ideas, L’Immensitá projected in competition at the Venice Film Festival 2022 (#Venezia79) does not find its breath nor its link. The fault of a look of the most common … Penelope Cruz is invited here to play the Italian woman as a quasi ghost of Sofia Loren, in a coarse and supported, without the charm of divorces and Italian marriage, which said a lot about an era, but also and especially Italy.

The identity theme, the gender binarity, seems to occupy the story on the same level as the other theme, however unrelated: the submission of a woman, the abuse of her husband and the complicity of his entourage. The attempted mixture does not work very well for the good and simple reason that the relationship of cause and effect that is perceived is in the worst taste … As can be one of the collateral disorders on one of the children, who starts to defecate in front of the door of the marital room to indicate his distress. Rude, once again.

The narrative strings, the protruding seams, do not allow us to hang on to this story which develops without any other goal than to push the door open on its strong subjects since they are in the air of time. The few good ideas of staging or script, more or less successful, do not allow us to hang on to the whole. Thus, the fact of inviting in the story the aspirations to a liberation, the references to very Italian images, of yesterday (for example the social and ethnographic frontiers very often put on the screen by Pasolini or Scola) or of today and maybe even more the will to wrap the whole in a musical fantasy universe interest us temporarily but end up tiring, again the fault of this look lacking singularity despite the beautiful intention to pay tribute to a cinema so distinctive, and which, in its time, traced its own way, to better compete and dialogue with the proposals of French cinema.

We keep in mind one of the rare moments when the film ventures on the side of subtlety, when the deeply wounded woman, who seeks with her children to recreate a childlike universe where good humor reigns, observes not without cynicism to her mother-in-law that she « is not afraid of the fantasies of children, but is much more suspicious of the fantasies of adults. This rare insight, this intelligent remark among other dialogue attempts, otherwise more common, ends up convincing us that the secondary subject should have been the main one, that it was enough on its own, and that marrying it to a period cause, which we do not deny the interest of being conveyed as such, harms much more than it brings.