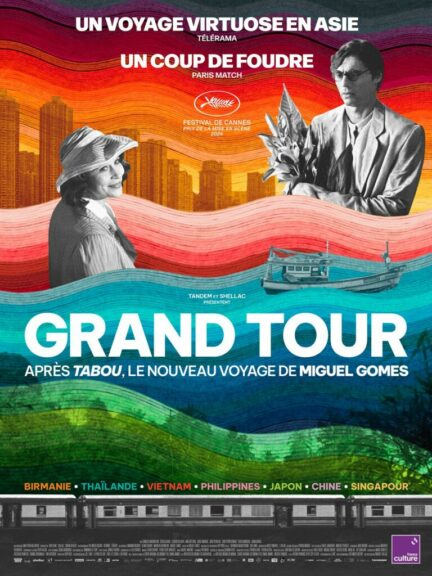

A film by Miguel Gomes

With: Gonçalo Waddington, Crista Alfaiate, Cláudio da Silva, Lang Khê Tran, Jorge Andrade, João Pedro Vaz, João Pedro Bénard, Teresa Madruga, Joana Bárcia, Diogo Dória

In 1917 Burma (now Myanmar), a British diplomat is set to marry his fiancée, but after a sudden panic, escapes to Singapore, sending her on what evolves into a chase across Asia

With Grand Tour, Miguel Gomes‘s selection debut, he takes a break from the very long running time of A Thousand and One Nights, returning to a format closer to that of Taboo. As he himself describes it, his primary intention is that of a journey. To propose a journey that he himself would have made. His Moby Dick, somewhere. Romanticized in the form of a stalker, the process allows him to observe and stop at the various ports of call he proposes, here or there, then or now. The process of the Grand Tour (going from one former British Asian colony to another) also allows him to experiment with encounters – and non-encounters! – between different countries, different cinemas, starting with his own, and memories he might have of other filmmakers who have narrated these same territories. The process also slightly blurs the boundaries between fiction and documentary, past and present, with Gomes simply filming in the present, applying a black-and-white filter to the fictional images, leaving in color those specific to the dream of the man on the run – rather critical visions of the future on the whole, and shooting the interior scenes in the studio.

For Gomes, suspending time also means pausing on snippets, moments borrowed from other filmmakers, allowing the critics who love them to note here and there images and sequences linked to Hsao Hsien, Yang, Ozu or Kurosawa, Oliveira or Ruiz, among many examples. The dialogues, too, play with these temporal registers, blurring reference points in small ways (from the pompous language of the colonial era to the more accepted vulgarity of our own time, a laugh that can be heard or a whistle to mask commonplace insults).

If the film, in its more narrative and feminine side, becomes pleasant – without ever dazzling – to follow once the long exposition is over (pedagogical without wanting to be, the quality of the images and the lack of variety in the proposals make us fear a pure experimental film that plays with amateur images ), However, the film suffers from the patchwork effect it creates, even if Gomes is not as flashy or electric as Tarantino, for example, who likes to incorporate cinephile references into his own work. Nor, like Honoré, does he opt for a marked-out, highlighted path that would tell the viewer, see here I’m talking about a film by Visconti, Antonioni or Fellini. His process is much more like a lighter, more discreet gesture (which delights treasure-seeking critics), relying on little bubbles or pastilles slipped in here and there. Except that this same process deprives us of a more global reading and approach to Gomes, one that would carry us away. In short, to make the poetry come through less artificially, we would have preferred it to emanate, in other proportions, from Gomes‘ own words and images.Because, in the end, this Grand Tour, like the accelerated tourist trips, tells us very little about a country, a city, only a few postcards – we retain the ones that speak to us – feed our memory, where, on the contrary, a Hsao Hsien, a Yang, to quote the filmmakers of the Taiwanese new wave, captured with great accuracy and patience (we could just as easily evoke the work of Zhang-Ké, Wang Bing) the past, the mutation in the making, and the frontier left between the two.