A revolutionary militant, a thug, an underground writer, a butler to a millionaire in Manhattan. But also a switchblade-waving poet, a lover of beautiful women, a warmonger, a political agitator, and a novelist who wrote of his greatness. Eduard Limonov’s life story is a journey through Russia, America, and Europe during the second half of the 20th century.

Limonov, the ballad, the long-awaited adaptation of Emmanuel Carrère‘s novel by Russian director Kirill Serebrennikov, was brilliant in parts, excellent overall, but frustrating in others. In the first place, it’s a shame that certain aspects of his character were left out (his French period, his taste for social occasions, his dealings with the media and the persona he created for himself, which was well documented, )! But it’s also a pity that his literary work and successes, his political actions, his opposition to Putin, his ultranationalism and his role in Russian political life are reduced, sometimes to a few images or words, where we would have preferred more development. So much for our initial dissatisfaction with the novel’s strength and Serebrennikov‘s mastery of punk and graphic art.

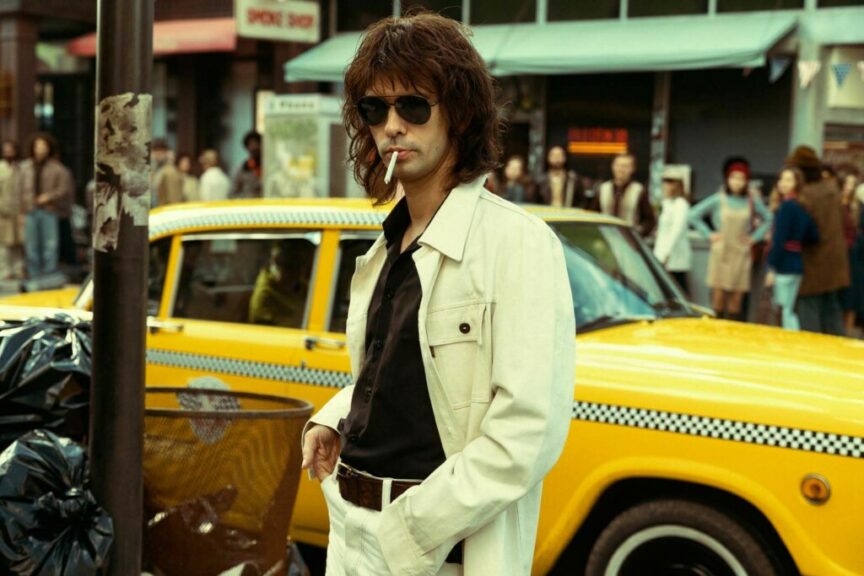

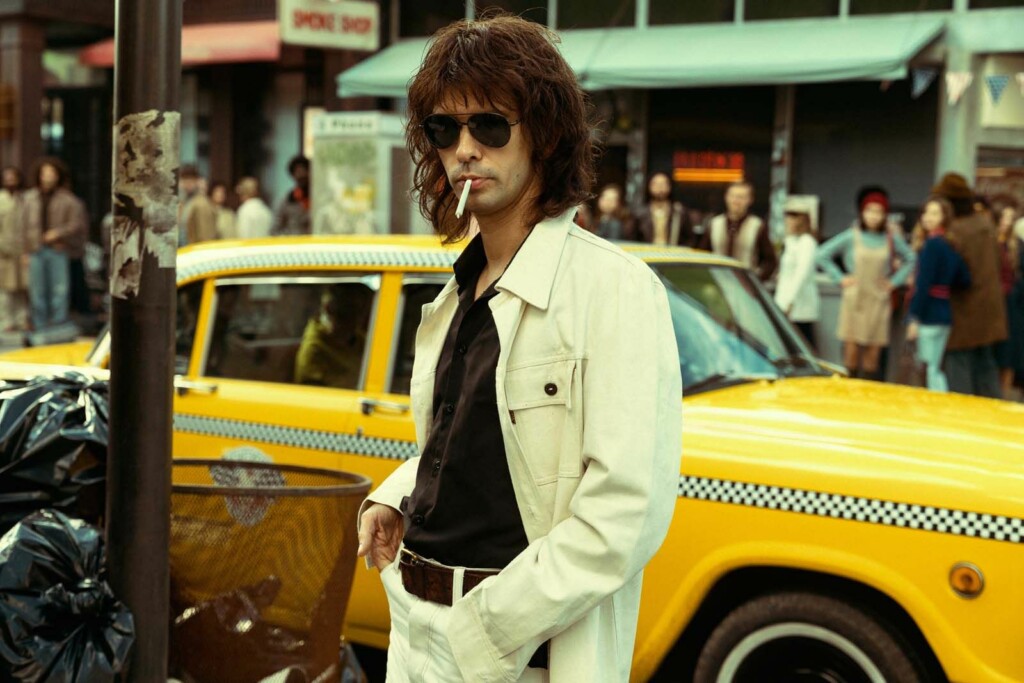

For, like Schrader, who returns to the Croisette with a work that relies on his contained talents, Limonov, taken in disconnection from the novel and from what we know of the poet Limonov’s intriguing life, richly deserved to be in the official selection at Cannes, and we’d wager that the film would leave the festival with an award. More precisely, Limonov is a concentrate of Serebrennikov‘s visual and sonic grammar, which finds here a subject and a trajectory where his talent can be expressed with excellence. Serebrennikov’s choice to immerse us in Limonov’s brain perfectly delivers the desired sensations, if that needed proving. The transformed Ben Whishaw gracefully embodies Limonov’s tortured mind, while the schizophrenic voice-over introduces us even further into his brain, in an immersion process already seen in Petrov Fever.

We also find this ambivalence (excellent but frustrating) in considering the soundtrack alone. Lou Reed and Tom Waits (Russian Dance) were the obvious choice as markers of the era and state of mind… but both lack the originality to reinforce Emmanuel Carrère’s epic text.

In addition to our reservations about the novel’s adaptation (impossible, let’s face it), Limonov seemed to us to suffer from the chosen (or forced?) pace. The film itself turns out to be either too long to concentrate the epic (or the ramblings of the poet’s soul), or too short to offer us a total art film or underline even more the extraordinary destiny of this man, his madness and what it reflects back to us. Frustrating, too, that the brilliant Russian director dwells so much on a love relationship that seems almost to be a primary wound, when the novel gives it very little importance. Frustrating that the magnificent idea of inviting Emmanuel Carrère to the cast is not pushed to its limits. Finally, it’s frustrating to find fault with a film that has a beautiful form and a diamond in the rough, and that we’re not talking here about an indisputable masterpiece, but only about a beautiful, poetic, inhabited film, a ballad much more than a ballad.