This is the story of a woman named Chiara. She’s an actress, the daughter of Marcello Mastroianni and Catherine Deneuve, and for one summer, when her own life is in turmoil, she decides she’d rather live her father’s life. She now dresses like him, talks like him, breathes like him, and she does it so forcefully that the others around her start to believe it, calling her “Marcello”.

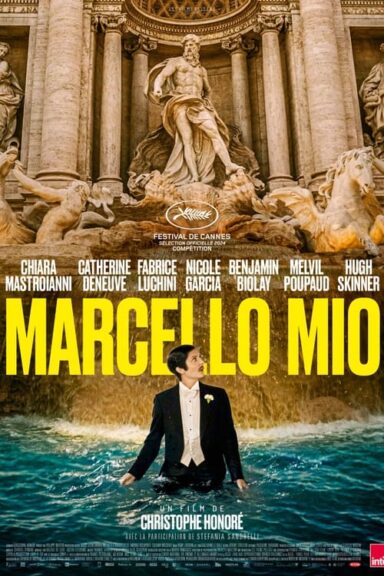

With Marcello Mio, Christophe Honoré finds an opportunity to indulge himself, both in the writing and, above all, in the setting. This infectious pleasure brings with it his muse, Chiara Mastroianni, and a number of guest stars from French cinema, including Nicole Garcia, Melvil Poupaud, Benjamin Biolay and Fabrice Luchini.

The whole thing is pleasantly surprising. Admittedly, the film possesses many of the attributes so often decried in French cinema (entre-soi, navel-gazing, bourgeois, intellectualo-parisiano-centric), admittedly we’re not dealing with a great work, or even a profound one, but the principle is highly playful, the concept ingenious and constantly renewed. Chiara’s disguise as her father is certainly not intended to be naturalistic; Honoré continues the surrealist gesture he began earlier, rather successfully, in Chambre 212, which at the time earned Chiara Mastroianni her first acting award (she had definitely ceased to be the daughter of) and led her to shed some very sincere and touching tears – we were very moved in return to see her so moved. Chiara and Marcello, in this virtual world reinvented by Honoré, are everywhere, occupying space and minds. As he traverses Mastroianni‘s life and work, Honoré draws on our memories, and Chiara’s own.

The Cannes Classics selection this year included a restored version of Robert Bresson‘s rare Quatre Nuits d’un rêveur, another film adaptation of the short story from Dostoyevsky’s Underground notes. The metaphor of the often absent father who the young girl misses so dearly operates with charm, and even as we grasp the principle, Honoré once again has fun abandoning it along the way to find other prisms to pay homage to Marcello’s filmography, even going so far as to parody Italian-style television and journalism. The rhythm of the comedy is constantly renewed, and scene after scene, shot after shot, we wait impatiently to discover the new stratagem that will allow us to tell the story of Marcello, his life, his work, his little secrets and pet peeves. Paradoxically, despite its apparent lightness, Marcello Mio has its less luminous side, intrinsic to Chiara’s fictional need to feel like herself.

In a subtle way, Honoré questions transidentity, or at any rate, the fact of not feeling perfectly oneself in one’s body as it is and aspiring, through fantasy, fantasy or vital necessity, to change. Without going too far into the psychological explanation, he also shows on screen the weight that appearances can have in this feeling. If Chiara could be tempted to turn into Marcello, as he imagines, wouldn’t it be because her features are naturally reminiscent of her father’s, just as an androgynous face contemplated daily in the mirror can remove certain markers as to a perfectly determined gender?

Clever, we say, and all this, by inviting the greatest names in Italian cinema, from Fellini to Visconti, via Comencini, Zurlini and Antonioni, to take a little trip to Italy from Paris, in small, admittedly touristy snippets, like Miguel Gomes‘ Grand Tour.