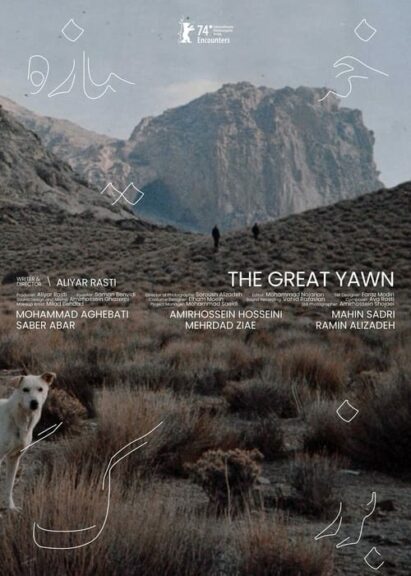

In an overall disappointing Berlinale edition, a little Iranian treasure emerged, The great yawn of history, on the edge between several very perceptible influences. These include Tarkovsky‘s mystical reflection on the landscape and the seasons, Purumbiu‘s (The Treasure), Kiarostami‘s initiatory quest (The Taste of Cherry), and Alice Rochwacher‘s Aliyar Rasti, who cites The Chimera as one of her primary influences (which may seem surprising given the short time between the two films). We might also add that the film could also remind us of a cinematic experience such as the one that animated Jean-François Stévenin, when he undertook Passe-Montagne. The film’s long, hard-earned running time gives way to a philosophical dialogue between two people struggling with the most profound existential questions, at once contrasting and similar. These two detached beings set off on a mysterious quest from which they both expect some form of revelation, rebirth and atonement. In any case, this story, heavily imbued with oriental mythology (we’re obviously thinking of The Thousand and One Nights and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves), offers a marvellous framework for extending another line of thought: what is cinema, at a time when techniques are converging, and the cinematic gesture, more than ever, tends to be lost under the pressure of the industry, more than ever eager to repeat a miracle recipe. The miracle, precisely, can only come from singularity, from a sincere and personal artistic gesture (Aliyar Rasti calls out to us when he evokes a retreat in the middle of the desert, in a caravanserai, which he undertook at a time when he himself was questioning his place on earth, his future and his dreams). The film left the Berlinale with a Jury Prize in the Encounters selection, and for us, was quite simply one of the only truly worthwhile films at this year’s Berlinale, which was singularly lacking in cinema.